Explore the 19 objects in this exhibition by clicking on the thumbnails of the objects that spark your curiosity - This will take you to detailed information about each one!

Scroll down for the full exhibition, or use the dotted menu bar on the right to jump to different sections.

This exhibition contains some explicit content. It is best viewed on a desktop.

When objects evoke strong feelings and reactions—be they wonder, intrigue, desire, confusion, fear, disgust, inspiration, comfort, safety or love—we gather, document and safeguard them.

When we assign symbolic or emotional significance to objects, they summon memories of meaningful people, places, hopes or experiences. An object’s intrinsic value is often beside the point; common, everyday items can be our most precious.

Every possession may accumulate layers of meaning: glamorous moments, terrible losses, romantic encounters, epic adventures, or hard-won achievements. Every object is the beginning of a personal or collective story.

At its most basic level, collecting is a universal human impulse. It is an ancient practice, despite the fact that most humans owned very few personal belongings before the Industrial Revolution made possible mass commercial culture and consumerism. Displaying collections for private and later public admiration is a more recent practice.

In the 16th century, rulers, nobles, scientists and prosperous merchants frequently maintained a Wunderkammer, or “cabinet of curiosities,” in which they stored and exhibited antiques, works of art, and natural, scientific and exotic remnants tending to the rare, eclectic and esoteric, such as corals or fossils. Historians consider such collections the precursors to modern museums.

This exhibition presents you with the GLBT Historical Society’s very own cabinet of curiosities, or, as we call them, “queeriosities,” drawn from our Art and Artifacts Collection.

With over 1,000 items, this is one of the world’s largest collections of two and three-dimensional objects that illustrate historical LGBTQ material culture. “Material culture” refers to physical objects, resources and spaces in the built environment that define, identify and reflect a group’s cultures, communities, behaviors, rituals, norms and perceptions.

The Art and Artifacts Collection contains paper materials such as drawings, pulp-fiction titles, sketches, architectural plans, and banners; metal objects such as pins, buttons, plaques, medallions, and badges; three-dimensional artifacts such as sculptures, paintings, historic business signs, and theatrical props; and textiles, such as costumes, uniforms, ribbons, and sashes.

These objects provide visual and material evidence of the San Francisco LGBTQ community’s engagement with the social, cultural, political and physical dynamics of the city, from the late 19th century to the present.

“The Art and Artifacts collection includes some of our most evocative, beautiful, and (yes!) strange items in the archives.

The collection has been growing for decades and we’ve worked hard to inventory it and bring it to the public.

The depth of creativity in the collection is amazing and we feel honored to preserve and share these pieces. Each item uniquely documents LGBTQ history.”

— The archives team,

GLBT Historical Society

The following carefully selected pieces from the Art and Artifacts Collection populate this special cabinet of queeriosities. Just as a Baroque prince inviting friends to view his cabinet of curiosities might have proudly explained each object’s background, we have provided information on each item’s provenance and historical significance.

These queeriosities include objects that highlight the struggles of marginalized communities within the greater LGBTQ community; materials that document hard-fought political battles; remnants of long-gone queer meeting places and sites of sociability; and items that are silly, irreverent and just plain fun.

The Art and Artifacts Collection is a growing, living assemblage, one of beautifully complex contradictions, much like the LGBTQ community that it documents.

Containing elements of beauty and ugliness, hope and despair, anger and joy, the collection evokes a range of ambiguous emotions. What provides coherence is the way each piece reflects multiple realities, experiences, fantasies and desires. All illuminate unique stories about LGBTQ people, our ever-shifting cultural landscape, and the ways we have forged our own identities, claimed our own spaces and constructed our own families.

Finally, there are also two objects in this exhibition—a personal collection of gloves and a blueprint for a mural—that are not officially part of the Art and Artifacts Collection, but are actually objects that are housed in separate archival collections. We include them not only to show off their artistic strengths but to explain that the Art and Artifacts Collection is not the exclusive repository of the artwork and artifacts in the GLBT Historical Society’s holdings; many of our other archival collections contain such materials.

Assortment of dildos, rubber latex, plastic and silicone, ca. 1980s; unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

Dildos and sex toys may be shocking to some or mundane household objects to others. Used for sexual stimulation and exploration, sex toys are not exclusively used by the LGBTQ community, nor are they especially novel; humans have manufactured them for hundreds of years. In the past two decades, sex toys have become more openly discussed and visible in popular culture and media. But they are still often considered taboo, and other than in pornography, their use is mainly private.

The private sphere is an important starting place for understanding what these dildos tell us about LGBTQ people and their history. Sexual exploration is a personal and private matter, enabling queer people to understand their identities, both alone and in relationships. Yet the private lives and sexual activities of LGBTQ people were, in effect, a matter of “public” concern throughout the 19th and 20th centuries as governments passed laws defining sodomy and sometimes other kinds of sexual acts as crimes. Rarely used to prosecute heterosexual people, such laws were explicitly intended to discourage homosexual relationships, and arrests of consenting couples could be and were made in private homes.

In the United States, these statutes remained on the books in many states until the 2003 Lawrence v. Texas decision, and they are still common around the world. Many religious faiths, including evangelical Christian denominations and the Roman Catholic Church, oppose sexual positivity of any kind, heterosexual or otherwise. Yet LGBTQ people are still particularly viewed and described as hypersexualized, suggesting an ongoing conservative and religious obsession with same-sex sexual activity coupled with the desire to discourage it.

These dildos from the 1980s, while not rare or otherwise remarkable, are surprising reminders of the battles LGBTQ people have faught to ensure their right to personal sexual freedom, exploration and self-care.

Ten bottles of poppers, empty containers of alkyl nitrate, ca. 1975; unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

“Poppers” is a slang term applied to a broad class of chemical psychoactive drugs in the alkyl nitrate family, originally isoamyl nitrate. A recreational drug, poppers are inhaled through the nose and produce an immediate “high” or euphoric effect by causing blood vessels to dilate and relaxing smooth muscles throughout the body. They are often used during dancing and sexual activity.

In contrast to the private nature of sex toys, poppers became associated with more open, public use by gay men in bathhouses in the early 1970s and spread to mainstream club culture over the course of the decade. During the early days of the AIDS crisis, poppers were criticized as contributing to the transmission of the disease, a hypothesis that was ultimately debunked. They are still commonly used by both LGBTQ and heterosexual people, but their legality and exact drug formulations vary from country to country. Poppers are often labeled as nail-polish remover, tape-head cleaner or indicated for other uses to avoid these jurisdictional drug laws.

Absolute Empress XVIII Connie’s vest, black leather covered with metal studs and her personal collection of enamel pins, ca. 1975–1995; unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

Can clothing and accessories truly define you or your community standing? Absolute Empress XVIII Connie of the Imperial Court of San Francisco (reigned January 9, 1983–January 7, 1984) thought so. Known as “the Siren,” “Temptress” and “Seductive Empress,” Connie wore imperial regalia as well as leather adorned with metal studs and pins to bridge the contrasting worlds of the Imperial Court and the leather community.

The International Imperial Court System is a network of charitable societies that use drag entertainment to build community and raise funds. Each court annually selects an Empress and Emperor. The first imperial court was founded in San Francisco in 1965 by José Sarria (1922–2013), who took on the name “José I de San Francisco, the Widow Norton,” a reference to the city’s beloved 19th-century eccentric Joshua Norton, who proclaimed himself Emperor of the United States in 1859. Like Connie, Sarria traversed multiple social spheres, performing in drag at the Black Cat in North Beach and in 1961 becoming the first openly gay candidate to run for public office in the United States.

Standing in contrast to the glitz and glamor of the Imperial Council, San Francisco’s leather and kink community emerged in the early 1960s. The South of Market (SoMa) district became home to this community, operating many bars catering to the motorcycle and leather communities and a famous leather and kink emporium, Mr. S. Leather, founded by Alan Selby in 1979.

Like José Sarria and Empress Connie, LGBTQ people navigate a world of distinct expressions, presentations and subcommunities that are interwoven in complex and personal ways. Clothing is a powerful means for self-expression and a way to signal community affiliation; our styles and garments evolve over time, like our identities.

Your turn!

What do you want to express when you choose to wear specific articles of clothing?

What might others think about who you are when they see you wearing them?

Two wool banners covered with buttons and pins, each panel 18.5” x 79”, ca. 1960–present; donated by Michael Armanini, with additions by various donors, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

These two banners of purple wool are adorned by hundreds of metal, enamel and plastic pins, all donated over the span of over 50 years by dozens of individual donors. Providing coherence to the assortment are the buttons’ shared function and LGBTQ themes; their eclectic graphic designs, familiar slogans and diversity of tone are seemingly as infinite and varied as the cosmos.

Buttons and pins, ca. 1960–present; donated by various donors, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

Some were produced by local groups and organizations or distributed at protests and community events. Others were novelties manufactured for shops or as souvenirs. For every pin that is firmly anchored in a specific time and place—such as the annual San Francisco Pride celebration, the election of Harvey Milk in November 1977, the No on Proposition 6 campaign of 1978 and No on Proposition 8 campaign of 2008, and ACT UP demonstrations of the late 1980s—there are dozens of timeless examples. These are replete with inside jokes, reclaimed derogatory terms, cheeky quotes, provocatory statements, harsh denunciations, explanatory pronouns and self-identifying terms signaling gender identity and expression.

The button panel displays are proudly hung on the wall of the reading room at the GLBT Historical Society archives, where they continually receive new additions, rouse curiosity and spark conversations. Rather than telling the story of just one person’s experiences, this wall is the amalgamation of many. The collection is a living, growing, ever-richer assemblage of LGBTQ life that provides visual evidence about the historical power of self-expression and the importance of finding and creating a sense of belonging.

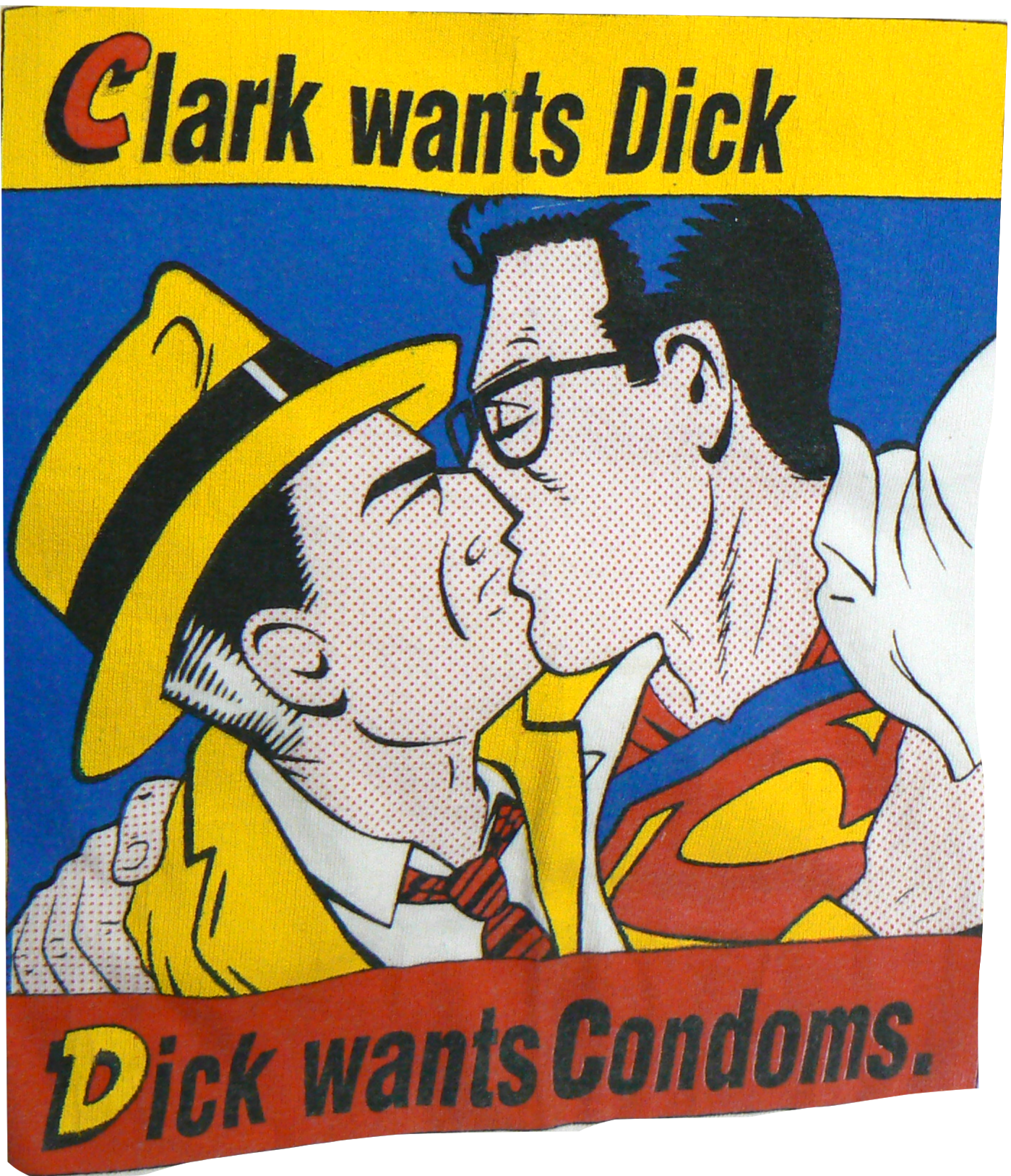

“Safe-sex” T-shirt featuring Dick Tracy, Superman, Robin and Batman, cartoon graphic screen print on cotton, ca. 1990; artist unknown, unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

The devastating AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s led to the development and promotion of “safe sex,” a set of harm-reduction strategies aimed at reducing the spread of sexually-transmitted infections, with an emphasis on condom usage. Emerging in the LGBTQ community in the mid 1980s, safe-sex advocacy and messaging became widespread very rapidly in the U.S. By the end of the 1980s, safe sex was widely reported on and promoted in television and print media, advertisements, public-service announcements, flyers, essays, cards and on tchotchkes and other ephemera.

LGBTQ organizations and supporters remained centrally involved in fostering safe sex in the community. This T-shirt is an example of the clever, creative messaging they deployed. The colorful, beautifully-drawn, screen-printed garment features instantly recognizable comic-book icons. In each panel, from left, Dick Tracy is kissing Superman, Robin and Batman, respectively. Playing on the word “dick,” the T-shirt does not discourage sexual activity, but cheerfully reminds the wearer to use “safe sex every time!”, suggesting that we follow the wise example of these familiar trench-coated and caped crusaders.

By pairing up stereotypically American, stolidly straight heroes as sexual partners, the design nods to the perceived homoeroticism of classic American comic books and to “slash fiction,” a genre of fan fiction that establishes romantic relationships between same-sex fictional characters. This incisive, irreverent approach uses humor to address a serious subject, breathing life into the often bland, repetitive and technical safe-sex messages that became ubiquitous during this time.

Ceramic Compton’s Cafeteria mug with brown drawn design approximating Compton’s wordmark, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot, 3” x 3”, 2016; unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

This ceramic mug is plain, almost homely, with its muted brown badge; yet its mere existence is a testament to the power of historical research to uncover hidden and unknown events and people at the margins whose stories must be told.

The badge on the front of the mug features a hand-drawn recreation of the wordmark of Compton’s Cafeteria. Compton’s was a chain of cafeterias owned by Gene Compton in San Francisco from the 1940s to the 1970s. The Tenderloin district’s Compton’s was located at 101 Taylor Street, at the corner with Turk Street, and was open from 1954 to 1972. Its patrons included numerous queer and transgender people, many of whom lived in the local single-room-occupancy hotels and made a living through sex work. The cafeteria, which was open 24 hours a day, provided a relatively safe space for transgender women, young male hustlers and others into the late hours of the night.

One evening in August 1966—historians still have not determined the exact date—patrons of the cafeteria reacted violently to police harassment. Transgender women and drag queens threw crockery and overturned tables as they fought with police who were trying to evict them from the restaurant, shattering its windows in the process. The incident, which took place three years before the well-known Stonewall Riots in New York, was one of the first LGBTQ uprisings in U.S. history. Despite its significance, unlike Stonewall the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot was nearly lost to history, as there was virtually no reporting about the incident at the time and little documentary evidence survives. Even mere photographs of the exterior or interior of the cafeteria are extremely rare.

Our archives contain much of the documentation of Compton’s that does survive, which enabled transgender historian and former GLBT Historical Society Executive Director Susan Stryker to piece together its history in the early 2000s. Stryker describes the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot as “the transgender community’s first act on the stage of American political history.” By the 50th anniversary of the riot in 2016, Compton’s had become sufficiently well known to inspire the creation of this commemorative mug—a testament to the growing awareness of transgender history and acknowledgment of its significance.

The Lesbian Avengers (San Francisco Chapter) demonstration banner, cloth canvas with painted phrase “The Lesbian Avengers. We Recruit” and cartoon drawing of a bomb, 4’ x 7’, ca. 1992; unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

Activism has been a key focus of LGBTQ people since the first gay-rights organizations emerged in the 1950s. Activists use a plethora of strategies to draw public attention to pressing problems, social issues and injustices, seeking to educate and inform, provide clear terminology, promote authenticity and increase visibility, often showing up for those who cannot. Their tactics include protests, public demonstrations or direct-action approaches. Direct action tactics are distinguished from organized marching or public speeches; they ignore established or institutionalized actions and can include unannounced appearances, sit-ins, strikes or street blockades. Activists also often deploy art and creativity, often laced with humor, to create signs, flyers, newsletters or banners like this one.

San Francisco Dyke March picket sign, red cardboard poster featuring white text and a black silhouette of an open hand with the words “No Retreat!” 1996; design by Lisa Roth and Fireworks Grafix, unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

The banner was created by the San Francisco chapter of the Lesbian Avengers, a direct-action group founded in New York in 1992 and led by Ana Maria Simo, Sarah Schulman, Maxine Wolfe, Anne-christine d’Adesky, Anne Maguire and Marie Honan. At a time when government and media coverage of LGBTQ people focused predominantly on cisgender, white gay men, the Lesbian Avengers focused on issues that were deemed vital to lesbian survival and visibility, including abortion rights and the impact of HIV/AIDS on women. Defiantly protesting sexism and misogyny, they specialized in peaceful, if provocative street entertainment, with a flair for the fun and theatrical. For instance, to “recruit” members at Pride parades, they created guerrilla-style banners, flyers and club cards stamped with images of exploding bombs and the slogan “Lesbian Avengers: We Want Revenge and We Want It Now!” Dozens of other Lesbian Avenger chapters, including a sizeable one in San Francisco, formed worldwide before the organization’s dissolution in 1997.

The Lesbian Avengers’ work led to the founding of the first Dyke March in Washington D.C. on April 24, 1993, as part of the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. Over 20,000 women joined together to march from Dupont Circle to the White House. Nearly 30 years later, the Dyke March has been replicated in cities across the country and now traditionally takes place on the day before the Pride Parade in June. The San Francisco Dyke March has been bringing dykes and women together every year since 1993. With the help of vibrant handmade banners and picket signs like this “No Retreat” example from 1996, Dyke March participants oppose racism, sexism, homophobia, and poverty.

Your turn!

What kind of tactics would you be willing to use to support the causes you care about the most? What kind of ideologies and opinions would you seek to change?

The Penniless Princess, Jerome Caja (U.S., 1958–1995), mixed media collage, 9” x 12”, 1990; donated by Gerard Koskovich, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

The Penniless Princess wears a white blouse and stands with an inscrutable expression on her face, holding her pants pockets turned inside out—a classic cartoon iconography showing "I don't have a penny in my pockets"—directly above a bizarre scrap of paper advertising the positive impact that donations of $25 to $1,000 to “Mamma Clara” can be expected to have on worthy lepers. Who is this woman? A princess? A leper? Mamma Clara? Or is she a symbol that requires interpretation, daring us with those intense eyes?

Jerome Caja (1958–1995) was a queer, Cleveland-born and San Francisco-based visual artist and drag performer. His radical work consistently challenged heteronormative conventions and raised awarenss of LGBTQ issues, particularly the ongoing AIDS crisis. Best known for his mixed-media paintings using everyday materials—often those associated with femininity such as nail polish, lace and glitter—Caja’s artwork also frequently incorporates Greco-Roman and Catholic iconography. During his lifetime, Caja’s work was featured in numerous gallery shows and in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s 1991 exhibition Facing the Finish: Some Recent California Art.

According to Anthony Cianciolo, director and founder of The Jerome Project, an effort dedicated to preserving Caja’s remarkable artistic legacy, The Penniless Princess is actually a portrait of American writer and musician Adam Klein. Klein later coauthored a monograph about Caja entitled Jerome: After the Pageant (Bastard Books/Distributed Art Publishers, 1996). Yet the work also departs from the conventions of portraiture, and the central figure seems to transcend a depiction of a particular person. Caja died in 1995 at the age of just 37 due to complications from AIDS, but his brilliant, transgressive reputation continues to grow, thanks to what The Jerome Project describes as the artist’s “unapologetic, raw, sexual, humorous, and honest” qualities.

This remarkable collage was purchased in 1990 by Gerard Koskovich for $25 at a gallery show entitled “Jerome’s Compact: Little Lovelies at the Art Lick Gallery” and later donated to the society. Caja’s work is now highly sought-after and is found in major museum collections and archives around the world, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), the New York Public Library and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). His papers are held by the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Portrait of Ambi Sextrous, Doris Fish (Australia, 1952–1991), acrylic on canvas, 16” x 19”, 1978; donated by Ms. Bob Davis, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

Her mouth open in exaltation, white teeth flashing in her blue beard, wrapped in an orange boa and wearing her signature necklace of miniature human skulls, drag performer Ambi Sextrous is framed by clouds, a rising sun and a rainbow in this fantastic, color-saturated portrait by Doris Fish.

The stage name adopted by Philip Mills in 1972, inspired by actress Doris Day and a cat named Lillian Fish, Doris Fish arrived in San Francisco from Australia in 1976. Fish was a talented artist and drag performer who performed with Ambi Sextrous, a blue-bearded “genderfuck” drag queen performer. Ambi produced several full length solo shows of her own and was a well-known figure at street fairs and community events. She performed alongside Doris Fish in both the theater troupe Sluts A GoGo and in the 1991 cult film Vegas in Space, a science-fiction comedy.

In a spring, 1978 entry in her personal diary shown here, Ambi included the snapshot that gave birth to the portrait, noting “this photo inspired a soon to be famous acrylic on canvas painting by Doris Fish.” Fish’s completed portrait, though painted in 1978, prefigures the profound change that occurred in San Francisco’s queer nightlife and art scene in the mid-1980s as the accelerating AIDS crisis struck down artists and performers. In flamboyant acts of resistance and excess, members of the community responded to the stigma of AIDS and homophobia by making themselves, and their work, even more visible, colorful, outspoken and outrageous. This portrait depicts Ambi Sextrous as proud, unafraid, and optimistic; the clouds on the horizon seem to be clearing and moving away, not coming toward her.

Doris Fish passed away in 1991 and Ambi Sextrous in 1992, both from AIDS.

Tummy Glow Tinky Winky, stuffed, plush soft toy packaged inside its original box, created by Hasbro Playskool, approximately 4” x 8”, 1998; unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

Tinky Winky was one of the four stars of the popular 1997 British children’s television series Teletubbies, and his induction into LGBTQ history is a story of reclamation. The loveable purple character was “outed” in 1999 by Jerry Falwell, Sr., the well-known pastor, televangelist, and founder of Liberty University. In a National Liberty Journal article entitled “Parents Alert: Tinky Winky Comes Out of the Closet,” Falwell accused the cute fellow of being a gay role model who could be morally damaging to children. Tinky Winky’s undercover identity was supposedly evident because “he is purple, the gay-pride color; and his antenna is shaped like a triangle, the gay pride symbol.” Apparently Tinky Winky’s stylish bag was also a mark against him.

News of the “controversy” exploded across media and the internet, with Falwell being openly ridiculed. Yet members of the LGBTQ community responded in force, embracing the sweet purple guy as one of their own, flocking to purchase Tinky Winky merchandise and emptying store shelves in the process. “If he wasn’t [gay] before, he is now,” quipped a collector, as reported in the New York Times. Our own Tummy Glow Tinky Winky—still in his original packaging!—dates from this era of enthusiastic queer appropriation.

But the entire affair had a sinister side that went largely undiscussed: it repackaged and redeployed the myth of LGBTQ people as predators who prey on children. It was surely no coincidence that Falwell drew a connection between queer people and a child’s doll depicting a character described as a toddler.

Though the Tinky Winky incident is now over 20 years old, conservative politicians, organizations and religious groups around the world remain obsessed with the supposed dangers associated with LGBTQ people. Particular attention in recent years has focused on the transgender community, with numerous state legislatures drafting anti-trans “bathroom bills.” The traditional predator myth is still a common theme, as evidenced by Russian government statements prior to the 2014 Sochi Olympics (“Stay away from the children,” warned President Putin); in Poland (which in 2007 considered reopening the Tinky Winky debate); and in Hungary, whose parliament ratified explicitly anti-LGBTQ laws in July 2021 banning the “promotion” of homosexuality in schools.

As for Tinky Winky, times have indeed changed. In 1999 the Teletubbies public-relations team quickly dismissed rumors of his sexuality; in 2021, the Teletubbies released a limited-edition Pride inspired clothing line, with all proceeds benefiting GLAAD.

Gay Monopoly, board game published by the Parker Sisters, Fire Island Games Inc., ca. 1983; unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

One of the most popular board games of all time is Monopoly, which has been played by around one billion people since its introduction by Parker Brothers in 1934. There is seemingly nothing more emblematic of upright, heterosexual, individualist American capitalism than a game that has “the bank” in a starring role and sends players off to engage in ruthless property speculation with the aim of bankrupting their opponents.

Seeing an opportunity to give this popular, if traditional, game a queer twist, a company called “Fire Island Games” released a tongue-in-cheek, totally unlicensed and unauthorized version in 1983 called “Gay Monopoly: A Celebration of Gay Life,” irreverently signed by the “Parker Sisters.” That the creators put serious thought into the overhaul is evident from the box cover. It features the game’s mascot: a muscle alligator borrowed directly from the alligator logo of the preppy Lacoste polo shirts that were then in fashion among gay men. The comely crocodilian winks at the viewer while trailing knotted multicolored hankies in his back pocket, a reference to the colored hanky codes of the 1970’s.

The game creators reconstructed many of the elements of this classic game to cater to queer board-game enthusiasts. While Monopoly’s streets are located in Atlantic City, Gay Monopoly includes properties in LGBTQ villages and gayborhoods all over the United States, with Castro Street, Folsom Street and the Russian River representing the Bay Area. Houses and hotels become bars and bathhouses, reflecting the most widespread, safe queer spaces of the 1980s. The sense of community symbolized by the properties is reinforced by an added trivia element, “Family Pride” cards. These ask players to guess a famous LGBTQ person described in a short biography, connecting players to the legacy of LGBTQ community activism.

Gay Monopoly was short lived, since an unhappy Parker Brothers immediately sued the publisher for copyright infringement. Despite its cheerful, celebratory mood, the game unintentionally reflects dark clouds on the horizon. The Castro district would soon be known internationally not just as a gayborhood, but as the ground zero of the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco. Bathhouses became the center of a fierce political debate in the city the year the game was published, with opponents blaming them for contributing to the rampant spread of the disease, and were banned in 1984. Gay Monopoly is also firmly anchored in its specific time period and is notable for what it leaves out. It is primarily focused on and marketed to gay men, with little about lesbians and essentially nothing about transgender and nonbinary people.

Community is cultivated around common experiences and time spent together, and can be as simple as enjoying games that remind us of our shared identities. Through play, we can express emotions, channel difficult conversations or let go of hardships, even for a moment. Gay Monopoly and a half-dozen other LGBTQ-themed board games of the 1980’s provided opportunities for communal entertainment that subverted heteronormative social and family structures. The game’s playful, campy approach and focus on community places it in the long lineage of queer entertainment that continues with the remarkable international popularity of drag bingo, LGBTQ bar trivia evenings and show-tunes nights.

Your turn!

How would you give your favorite game a unique twist?

Which aspects from your daily life, or traditions would you incorporate? What kind of rules would it have?

Sylvester’s collection of antique gloves, leather, satin, and silk, ca. 1930s; wood frame and glass front 32” x 42”; donated by Bernadette Baldwin, Sylvester Collection (2018-05), GLBT Historical Society.

These rare leather, satin and silk gloves were worn by the revolutionary artist Sylvester (1947–1988), a famed Black disco performer and soulful singer-songwriter who gained mainstream fame during the disco era of the 1970s. Sylvester grew up in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles singing in church choir.

As a young adult, he moved to San Francisco in 1972, where he joined the celebrated genderfuck performance troupe The Cockettes and began his recording career the following year. After a string of successful albums in the late 1970’s, which included the internationally successful singles “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” and “Dance (Disco Heat),” he achieved global stardom and ultimately became known as the “Queen of Disco.” He died in 1988 of complications from AIDS, his legacy as San Francisco’s greatest disco diva assured.

From the earliest days of his singing career, Sylvester pioneered a high-profile, flamboyant fashion style and self-presentation that might now be described as genderqueer or genderfluid. His stylish costumes—made with luxurious fabrics and adorned with sequins—dispensed with heterosexual norms and defied the gender binary. He displayed this striking collection of elegant, vintage women’s gloves, complete with wooden frame, in his own home. According to his sister Bernadette Baldwin, who donated the collection, Sylvester had a particular fascination for antique gloves and enjoyed incorporating them into his costumes. They were not mere accessories; these gloves reflect Sylvester’s own collecting hobbies, personal taste and commitment to his identity. They are also a reminder of a man who, by fearlessly transgressing racial, sexual and gender boundaries, inspires us to shatter cultural ceilings and dares us to feel boldly confident in our own skin—to unleash our own superstardom!

Your turn!

Sylvester loved collecting gloves; what do you enjoy collecting?

What does your collection say about your personality and tastes?

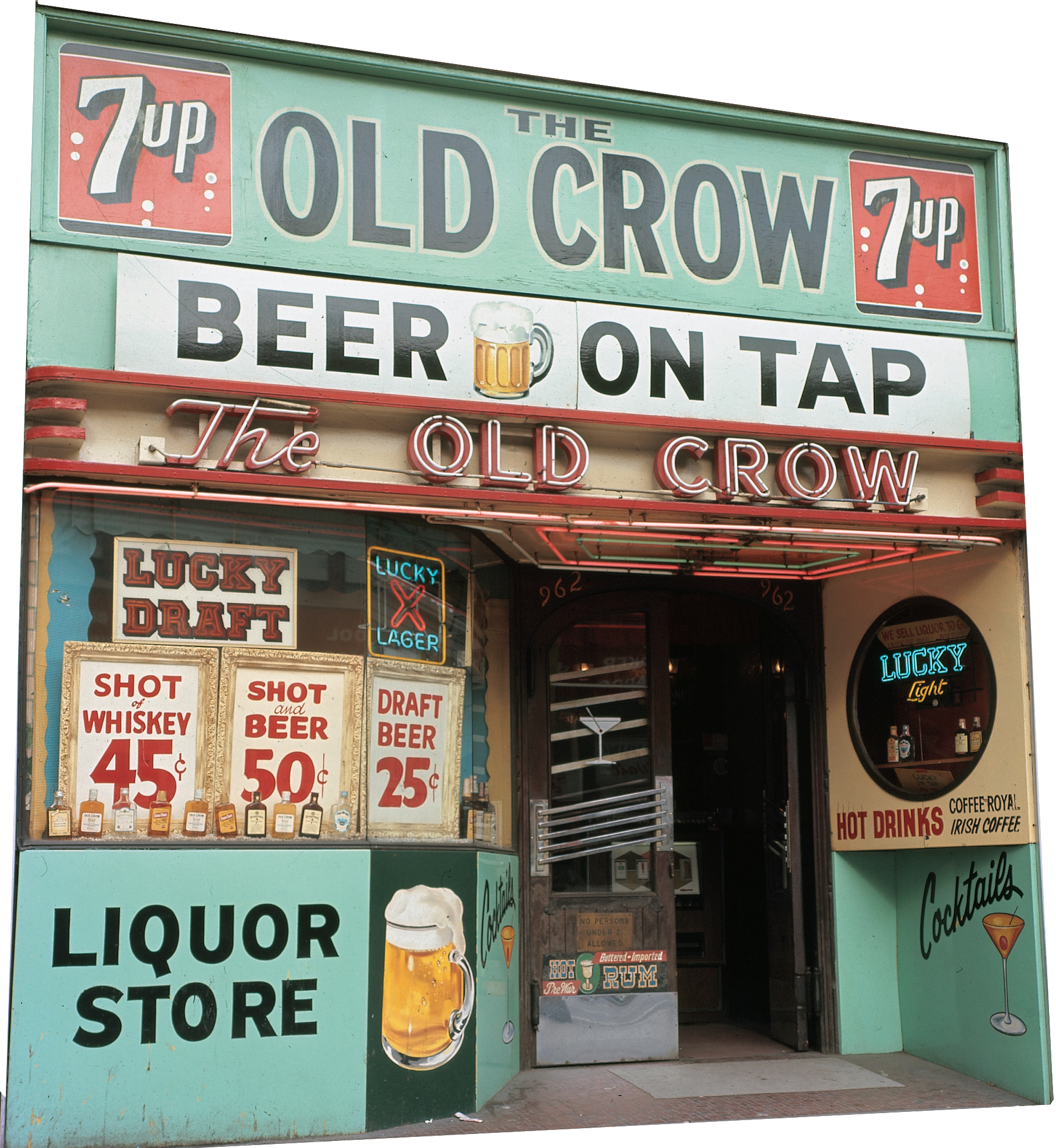

The Old Crow bar sign, painted wood mounted on metal in two sections, each letter approx 12” x 50”, 1935–1980; unknown provenance, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

The exterior of the Old Crow bar at 962 Market, San Francisco, ca. 1960s–1970s; photo by Henri Leleu, Henri Leleu Papers (1997-13), GLBT Historical Society.

This unprepossessing, chipped business sign once stood at the entrance to a small tavern located at 962 Market Street, between 5th and 6th Streets, from 1935 until its closure in 1980. The building that once housed the bar is located just steps from the GLBT Historical Society’s current archives and offices. The bar itself was a small, rather rundown and seedy-looking establishment, an appearance possibly cultivated intentionally to minimize police surveillance.

The battle-scarred sign and the Crow’s quiet longevity are instructive: it is impossible to overstate the central importance of bars, taverns and cabarets to the LGBTQ community, even discreet, low-key establishments tucked into storefronts.

For decades, these establishments provided some of the only consistent, relatively safe spaces for queer people to gather, socialize, organize and fall in love. Despite constant raids by agents of the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board and other regulatory agencies, and frequent, sustained police harassment, bars provided a space where queer people could be reasonably open about their identity and sexuality, and find others like themselves.

Amelia’s bar sign, backlit lightbox sign with white panel, 4’ x 6.5’, ca. 1978; donated by Mary Sager, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

Bars cater to specific LGBTQ subcommunities and demographics. Though often associated strongly with gay men, they have been equally important to women, though the number of lesbian establishments has been dwindling around the country for the past two decades. Amelia’s was the first supposedly “last lesbian bar in San Francisco,” causing a stir when it closed 30 years ago. Located at 647 Valencia Street in the Mission District, the beloved lesbian dance bar operated from 1978 to 1991 and was owned by Rikki Streicher, a lesbian activist, businesswoman and cofounder of the Federation of Gay Games. Under her direction, Amelia's sponsored the first women’s team in the Gay Softball League. The club was one of several establishments catering to lesbians in the Valencia Street corridor from the 1970s through the 1990s. The space’s connection to LGBTQ history goes back even further: In the early 1970s, it was home to a nude male go-go bar, the Gaslight.

Photograph of Amelia’s sign temporarily installed on the Elbo Room, courtesy of Evie Blackwood.

From 1991 to 2015, the space operated successfully as the Elbo Room, a much patronized local dive bar. After its closure, there were scary rumors that the building would be torn down, but today the establishment is home to the Valencia Room, a spiffed-up descendant of the Elbo Room. In 2018 the GLBT Historical Society received the exterior sign of Amelia’s, which the Elbo Room had faithfully preserved and displayed annually for nearly 25 years.

Assorted matchbooks containing paper and wooden matches, ca. late 1970s–1980s; various donors, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

At one time, many Americans collected matchbooks, displaying them in glass bowls on kitchen countertops or sideboards and occasionally dipping into them to light cigarettes or candles. Bars, taverns, restaurants, clubs and all produced the colorful packets in massive numbers, each stamped with their logos and wordmarks, and adorned with addresses and telephone numbers. The practice of matchbook collecting is known as phillumeny—and these small, folded pieces of cardboard tell unique, overlooked stories, with the power to document the changing face of an entire city.

Matchbooks are classic examples of ephemera: cheap, mass-produced everyday objects that are usually made of paper and are typically discarded after use. Their lack of intrinsic value belies their irreplaceable value as documentation of long-gone LGBTQ spaces and sociability. The matchbooks provide information about business locations, proprietors and even, through their illustrations, logos and epigrams, provide clues to the establishments’ atmosphere or intended audiences.

Patrons might have exchanged phone numbers or addresses by scribbling on the nearest matchbook. There’s no way to estimate how many friendships and relationships might have formed because a matchbook got passed from one person to another, or how many matchbooks were retained as keepsakes, souvenirs from a night out or reminders of a special someone.

Once ubiquitous, matchbooks are uncommon today; manufacturing peaked during the 1940s and 1950s and declined thereafter, due to the availability of disposable lighters and the emergence of anti-smoking health campaigns, though some establishments continue to provide them into the 21st century. Each example documents the historic and cultural significance of a bygone era, but also symbolizes LGBTQ people’s lived experiences and the networks of safe spaces that gave rise to memories and hopes.

Design for the MaestraPeace mural on the Women’s Building, color pencil drawings on vellum paper, 29.5” x 40”, 1992–1994; mural designed and painted by Juana Alicia, Miranda Bergman, Edythe Boone, Susan Kelk Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton and Irene Perez; MaestraPeace Artworks Records (2008-50), GLBT Historical Society.

The San Francisco Women’s Centers (SFWC) emerged out of the radical feminist and lesbian movements of the early 1970s. In 1973, two women started an office in their home with the goal of using the SFWC’s nonprofit status to fundraise and sponsor projects organized around women's issues. The next year, SFWC moved into a tiny storefront office at 63 Brady Street shared with the San Francisco Women's Switchboard, hired its first paid staff member, and became a membership organization with its own newsletter.

In 1979, the group bought Dovre Hall on 18th Street in the Mission District and transformed the four-story building into the first woman-owned and operated community center in the country: the Women’s Building. Over the past four decades, the Women’s Building has sponsored more than 170 organizations—many growing into established nonprofits, such as, La Casa de las Mujeres, San Francisco’s first shelter for battered women; the Women's Foundation of California; and Lavender Youth Recreation and Information Center (LYRIC). One of the co-founders of the Women’s Building was Carmen Vázquez (1949–2021), a longtime LGBTQ, social justice, immigration, reproductive justice and sexual freedom advocate who was born in Puerto Rico and grew up in Harlem, New York City. She helped found LYRIC and the LGBT Health & Human Services Network, for which she served as director. Today, the Women’s Building is an anchor institution in San Francisco’s ever-changing Mission District, welcoming 25,000 clients and visitors each year who use its in-house programs to gain access to social services, attend workshops and meetings, take wellness classes, volunteer, hold celebrations and deepen their community connections.

Many San Franciscans know the building principally for the spectacular, colorful MaestraPeace mural painted in 1994 that is five stories high and covers two sides of the building. This intricate, detailed scale drawing of the building was executed during the planning stages of the MaestraPeace project. The magnificent collaborative piece of public art was painted by seven multigenerational and multicultural muralists—Juana Alicia, Miranda Bergman, Edythe Boone, Susan Kelk Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton and Irene Perez—the mural depicts the power and contributions of women throughout history and around the world.

MaestraPeace mural on the Women’s Building, 1992–1994; mural designed and painted by Juana Alicia, Miranda Bergman, Edythe Boone, Susan Kelk Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton and Irene Perez; MaestraPeace Artworks Records (2008-50), GLBT Historical Society.

The mural blends with the cultural and historic fabric of the Mission District, home to one of the largest Latino and Hispanic populations in San Francisco. Large numbers of Mexicans began settling in the area during the 1940s. Local artists in the Mission have been inspired by multiple influences, including the Mexican Mural Movement of the 1920s, whose goal was to make art accessible to the people; and subsequently by the 1960s Chicano Mural Movement, which established muralism as an important means to preserve and celebrate Latin American culture. Like an outdoor gallery, MaestraPeace honors this blending of traditions and artistic heritage through its vivid portrayal of women as artists, revolutionaries, nurturers and healers across time and cultures.

This drawing is part of an archival collection that documents the planning and execution of the MaestraPeace artwork. The society also holds an archival collection preserving the organizational records of the San Francisco Women's Centers/Women’s Building from 1972 to 2001, providing a comprehensive look at second-wave feminism in the city.

Francis (Frank) Jordan’s black leather shoe, right foot, men’s size 10, manufactured ca. 1991; presented by the “Shadowy Guardians of the Shoe” to Bad Cop/No Donut in 1992, donated by Bad Cop/No Donut in 1994, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

This is a man’s conservative black-leather loafer with decorative fringe and tassels. Our archivists have irreverently referred to this particular object as “Cinderella’s lost slipper,” but unlike Cinderella, its owner, former San Francisco Police Department Chief and former San Francisco Mayor Francis (Frank) Jordan, was never reunited with his shoe.

The story begins with Assembly Bill 101, a piece of legislation that would have guaranteed statewide protection from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. During his successful 1990 gubernatorial campaign, California governor Pete Wilson had indicated his willingness to sign the draft legislation. Governor Wilson’s veto of the bill on September 30, 1991 shocked and angered California’s LGBTQ population. While waiting for the news of the governor’s decision, Gerard Koskovich and Bob Smith had organized a gathering in the Castro district to either celebrate the bill’s signature or protest the veto peacefully. Approximately 8,000 to 10,000 people gathered on the block of Castro Street between 17th and 18th Streets.

“A staid, irretreivably unstylish leather loafer.”

Former San Francisco Police Chief Frank Jordan’s ill-considered decision to go to the Castro rally that evening—supposedly to express solidarity with the community—was an enormous blunder on the would-be politician’s part. Jordan had served as Chief of Police from 1986 to 1990 before resigning to run as the city’s mayor. In spite of his public support for AB 101, which he had urged Governor Wilson to sign, Jordan was largely viewed by LGBTQ people as a resolutely conservative, antigay cop. Police harassment had continued during his tenure, culminating in the Castro Sweep Riot of 1989—the single most massive police attack on LGBTQ people and people with AIDS in the city's history. This riot had taken place on October 6, 1989, when San Francisco police responded violently to a peaceful ACT UP march protesting government neglect of people with AIDS. Over 200 officers had invaded the Castro for more than three hours, beating activists and passersby, systematically sweeping all pedestrians from seven city blocks and placing thousands in businesses and homes under virtual house arrest.

With the memory of the Castro Sweep still fresh, the crowd was enraged by Jordan’s cynical and transparent attempt to win LGBTQ support for his mayoral campaign in the face of a devastating legislative loss. Militant protestors began heckling Jordan, pinned him against a plate-glass window and ultimately caused him to flee the neighborhood, injured and missing his right loafer. “I was pummeled and pushed and kicked and almost thrown through a window,” Jordan told the San Francisco Chronicle on October 2, which reported that Jordan had feared for his life.

This lost shoe is a symbol of decades of tumultuous, mutually antagonistic relations between the SFPD and the LGBTQ community. Its fate after the riot is one of high queer drama. According to the Chronicle, protestors at the time snarkily claimed that the loafer would “be fitted with a high heel and used in a voodoo ritual.” In fact, the shoe was displayed atop a doughnut box at the A Different Light Bookstore in the week following the riot, then disappeared into the hands of queer activists who preserved it until it was donated to the GLBT Historical Society, its appearance unaltered: It is still a staid, irretrievably unstylish leather loafer.

Stained-glass fragments from window at the Old State Office Building, formerly located at present site of 455 Golden Gate Avenue, San Francisco, 1991; donated by Brian Bringardner, Gerard Koskovich and Tom Icabone, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

This handful of colorful glass shards represents the second phase of the AB 101 Riot of September 30, 1991, which continued after Frank Jordan’s banishment from the Castro district.

Stained-glass fragments from window at the Old State Office Building with original mailing envelope, formerly located at present site of 455 Golden Gate Avenue, San Francisco, 1991; donated by Brian Bringardner, Gerard Koskovich and Tom Icabone, Art and Artifacts Collection (GLBT-ART), GLBT Historical Society.

The organizers of the Castro assembly had decided that in the event that Governor Wilson vetoed AB 101, the crowd would march to the New State Building, a California State office building located on Van Ness Avenue at the corner of McAllister Street. After assembling at this location, where speeches were made, some protestors continued two blocks east down McAllister to the Old State Office Building, located at what is now 455 Golden Gate Avenue. The protest veered out of control and turned violent after participants arrived to find the building surrounded by just a handful of police officers. Protestors set a corner of the building on fire (the corner they mistakenly believed contained Wilson’s office), trashed offices, burned property and in a final coup de grâce, destroyed the $60,000 leaded stained-glass window commissioned by former Governor Jerry Brown entitled “The Power of the Sun” that adorned the building’s main entrance. These broken glass shards are remains of the window.

The AB 101 Veto Riot was among the most massive LGBTQ riots in California history. One month later, Frank Jordan succeeded in winning the San Francisco mayoral election, but Pete Wilson changed his tune, signing Assembly Bill 101 in 1992.

While they no longer depict the California sun, these glass shards still illuminate a historical truth: The struggle for LGBTQ rights has taken place through legal and peaceful means as well as through riots and violence. Tied to a specific San Francisco location, the fragments enable us to engage in place-based history. Even though the Old State Building was torn down in 1997 and replaced the following year with the Hiram W. Johnson State Office Building, these pieces still have the power to transport us to the block of Golden Gate between Polk and Larkin Streets on a tumultuous, angry autumn evening.

Director of Exhibitions and Museum Experience, Website Design, Co-Curator

Leigh Pfeffer

Manager of Museum Experience, Public Programs

Meghan Pushee

Museum Exhibitions and Curatorial Intern

Mark Sawchuk, Ph.D.

Communications Manager, Editor, Co-Curator

Ramón Silvestre, Ph.D.

Museum Registrar and Curatorial Specialist, Co-Curator

Contact, GLBT Historical Society

The contents of this exhibition may not be reproduced in whole or part without written permission.